The impact of type 2 myocardial infarction on the 28 and 90 day prognosis of ICU patients with severe pneumonia

-

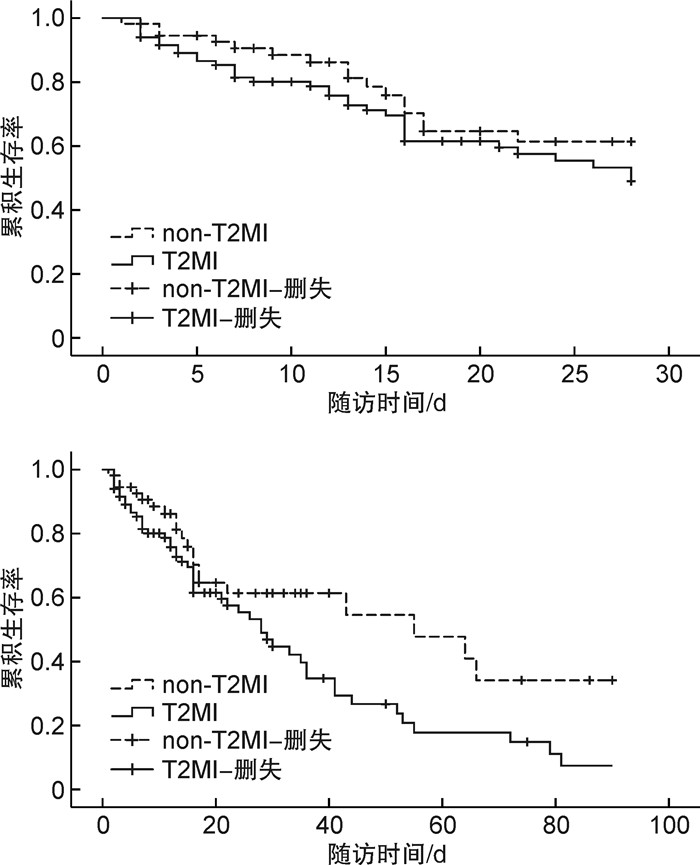

摘要: 目的 探讨ICU重症肺炎患者2型心肌梗死(type 2 myocardial infarction,T2MI)发生对其28 d及90 d预后的影响。方法 对2021年10月1日—2023年9月30日安徽中医药大学第一附属医院重症医学科诊治的重症肺炎患者共计139例进行单中心、回顾性、观察性研究。收集所有患者的一般人口学资料、疾病严重程度、实验室指标及T2MI的发生等临床资料,记录患者28 d及90 d的临床转归。根据患者28 d及90 d的转归情况分为死亡组和存活组,分别比较两组患者一般临床资料的差异,采用单因素及多因素logistic回归分析影响死亡的独立危险因素,并进行生存分析,绘制生存曲线。结果 纳入的139例重症肺炎患者中,T2MI的发生率为59.71%,28 d死亡率为35.97%,90 d死亡率为49.64%。相对于28 d存活组,死亡组的序贯器官衰竭(sequential organ failure score,SOFA)评分、血乳酸、随机血糖、胱抑素C水平均显著增高,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05);但T2MI的发生率之间差异无统计学意义(68.00% vs 55.06%,P=0.189)。相对于90 d存活组,死亡组的急性生理与慢性健康评分(acute physiology and chronic health evaluation,APACHE Ⅱ)、SOFA评分、血乳酸、血肌酐、尿素氮、胱抑素C、B型尿钠肽、降钙素原的水平均显著增高,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05);且与存活组相比,死亡组T2MI的发生率亦显著增高,差异有统计学意义(71.01% vs 48.57%,P=0.012)。单因素logistic回归分析发现,年龄、APACHEⅡ评分、SOFA评分、尿素氮及T2MI发生率是ICU重症肺炎患者90 d死亡的危险因素;进一步多因素logistic回归分析发现,SOFA评分(OR=1.865,95%CI:1.434~2.424,P<0.001)和T2MI发生率(OR=2.556,95%CI:1.060~6.163,P=0.037)是患者90 d死亡的独立危险因素;Cox回归分析发现,T2MI的发生对28 d死亡无显著影响(P=0.225),但相对于未发生T2MI的重症肺炎患者,发生T2MI患者的90 d死亡风险显著增加(P=0.029)。结论 ICU重症肺炎患者T2MI的发生率很高。T2MI的发生对患者短期预后无明显影响,但显著增加患者90 d的累积死亡风险。Abstract: Objective To explore the impact of type 2 myocardial infarction (T2MI) on the 28-day and 90-day prognosis of ICU patients with severe pneumonia.Methods A single-center, retrospective, observational study was conducted on 139 severe pneumonia patients treated in the Department of Critical Care Medicine at the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui University of Chinese Medicine, from October 1, 2021, to September 30, 2023. General demographic data, severity of the disease, laboratory indicators, and clinical data on the occurrence of T2MI were collected for all patients, along with the recording of clinical outcomes at 28 and 90 days. Patients were divided into deceased and surviving groups based on their outcomes at these intervals. Differences in general clinical data between the two groups were compared, and univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to identify independent risk factors for mortality. Survival analysis was further conducted, and survival curves were drawn.Results Among the 139 patients with severe pneumonia, the incidence of T2MI was 59.71%, with a 28-day mortality of 35.97% and a 90-day mortality of 49.64%. Compared to 28-day survivors, deceased patients had significantly increased sequential organ failure score (SOFA score), blood lactate, random blood glucose, and cystatin C levels, the difference was statistically significant (P<0.05), but no significant difference in T2MI incidence (55.06% vs 68.00%, P=0.189). However, compared to 90-day survivors, the deceased group showed significant increases in acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE Ⅱ)score, SOFA score, blood lactate, creatinine, urea nitrogen, cystatin C, B-type natriuretic peptide and procalcitonin levels, the difference was statistically significant (P<0.05). Moreover, the incidence of T2MI was also significantly higher in the death group compared with the surviving group, the difference was statistically significant (48.57% vs 71.01%, P=0.012). Univariate logistic regression analysis found that age, APACHEⅡ score, SOFA score, urea nitrogen, and T2MI incidence were risk factors for 90-day mortality in patients. Further multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that the SOFA score (OR=1.865, 95%CI: 1.434-2.424, P<0.001) and the incidence of T2MI (OR=2.556, 95%CI: 1.060-6.163, P=0.037) were independent risk factors for 90-day mortality. Cox regression analysis found that patients with T2MI had a significantly increased risk of 90-day mortality (P=0.029), though T2MI did not significantly affect 28-day mortality (P=0.225).Conclusion The incidence of T2MI is high among ICU patients with severe pneumonia. While T2MI does not significantly impact the short-term prognosis of these patients, it substantially increases their cumulative risk of death by 90 days.

-

-

表 1 两组患者临床资料比较

因素 总体

(139例)28 d预后 90 d预后 生存组

(89例)死亡组

(50例)统计量 P 生存组

(70例)死亡组

(69例)统计量 P 人口学资料 性别/例(%) 1.921 0.166 0.004 0.948 男 87(62.59) 60(67.42) 27(54.00) 44(62.86) 43(62.32) 女 52(37.41) 29(32.58) 23(46.00) 26(37.14) 26(37.68) 年龄/岁 74.37±1.39 72.46±16.22 77.89±15.78 1.869 0.064 71.01±16.81 77.92±14.86 2.514 0.013 合并症/例(%) 高血压 69(49.64) 46(51.68) 23(46.00) 0.218 0.641 35(50.00) 34(49.27) 0.007 0.932 糖尿病 48(34.53) 25(28.09) 23(46.00) 3.785 0.460 19(27.14) 29(40.03) 2.779 0.095 心功能不全 40(28.78) 28(31.46) 12(24.00) 0.544 0.461 21(33.33) 19(27.54) 0.018 0.784 心血管病家族史 15(10.80) 10(12.50) 5(10.00) 0.051 0.822 8(11.43) 7(10.14) 0.059 0.807 病情严重程度 APACHEⅡ评分/分 20.49±0.29 20.23±3.29 20.98±3.46 1.235 0.219 19.84±3.22 21.18±3.38 2.36 0.020 SOFA评分/分 5(4~7) 5(4~7) 7(5~8) -4.000 <0.001 4(4~5) 7(5~8) -5.415 <0.001 机械通气/例(%) 86(61.87) 53(59.55) 33(66.60) 0.147 0.078 39(55.71) 47(68.11) 0.542 0.144 实验室指标 血乳酸/(mmol/L) 2.5(1.4~4.55) 1.75(1.18~3.53) 2.90(2.13~4.70) -3.596 <0.001 1.60(1.00~3.60) 2.60(1.60~4.70) -2.991 0.003 白细胞计数/(×109/L) 9.96(6.99~17.17) 8.87(6.13~17.97) 10.88(8.35~16.66) -1.349 0.177 8.73(6.07~15.83) 10.59(8.19~19.18) -1.477 0.140 血小板计数/(×109/L) 165.79±7.53 163.82±89.28 163.67±12.87 -0.010 0.683 169.01±87.52 158.28±90.68 -0.704 0.960 中性粒细胞/(×109/L) 8.38(5.45~16.42) 8.16(5.06~16.99) 9.58(7.03~14.67) -1.317 0.188 8.06(4.91~13.63) 9.29(6.43~17.35) -1.647 0.100 淋巴细胞/(×109/L) 0.61(0.33~1.07) 0.55(0.28~0.92) 0.96(0.36~1.25) -1.155 0.248 0.56(0.29~0.93) 0.74(0.33~1.15) -0.512 0.608 入院随机血糖/(mmol/L) 7.01(5.69~10.32) 6.58(5.29~8.74) 8.26(6.51~12.36) -2.359 0.018 7.30(5.17~9.03) 6.84(5.69~11.73) -1.892 0.059 总胆红素/(μmol/L) 12.80(9.75~23.60) 12.25(8.97~21.23) 15.40(10.25~29.65) -1.094 0.274 12.90(8.60~21.60) 12.70(9.90~27.90) -0.250 0.803 白蛋白/(g/L) 30.07±0.48 30.27±5.39 29.70±6.32 -0.522 0.459 30.85±5.42 29.25±5.95 -1.625 0.875 尿素氮/(mmol/L) 11.18(7.48~16.32) 10.17(6.89~14.97) 12.55(10.01~31.47) -1.784 0.074 8.36(6.51~11.56) 13.74(10.39~30.22) -3.285 0.001 血肌酐/(μmol/L) 119.30(63.35~203.73) 86.75(60.35~207.25) 155.90(78.15~203.73) -1.870 0.061 74.00(56.40~180.40) 146.80(79.05~231.70) -2.696 0.007 胱抑素C/(mg/L) 1.63(1.15~2.93) 1.47(0.98~2.95) 1.86(1.30~2.88) -2.028 0.043 1.32(0.97~2.82) 1.90(1.26~3.09) -2.595 0.009 BNP/(mmol/L) 387.10(159.25~1 184.5) 363.80(112.50~1 096.03) 606.50(248.75~319.75) -1.398 0.162 264.00(101.00~498.00) 789.00(251.50~2 324.00) -2.423 0.015 D-D/(mg/L) 5.04(1.60~19.39) 4.63(1.52~15.08) 5.95(2.02~29.69) -1.779 0.075 4.84(1.45~16.75) 5.24(2.02~26.49) -1.743 0.081 PCT/(ng/L) 1.24(0.33~8.91) 0.81(0.22~8.75) 1.72(0.45~11.70) -1.373 0.170 0.42(0.19~6.95) 1.70(0.50~17.19) -2.008 0.045 CRP/(mg/L) 76.34(17.75~159.73) 63.00(17.05~123.93) 86.36(30.13~179.76) -1.587 0.113 47.77(15.96~108.08) 98.30(21.42~171.69) -1.682 0.093 表 2 重症肺炎患者28 d及90d不同预后T2MI发生率比较

例(%) T2MI 总体

(139例)28 d预后 90 d预后 生存组

(89例)死亡组

(50例)统计量 P 生存组

(70例)死亡组

(69例)统计量 P 发生 83(59.71) 49(55.06) 34(68.00) 1.724 0.189 34(48.57) 49(71.01) 6.372 0.012 未发生 56(40.29) 40(44.94) 16(32.00) 36(51.43) 20(28.99) 表 3 重症肺炎患者90 d死亡的logistic回归分析

因素 单因素 多因素 OR P 95%CI OR P 95%CI 年龄 1.029 0.015 1.006~1.053 1.015 0.240 0.990~1.042 APACHEⅡ评分 1.122 0.030 1.012~1.245 1.041 0.535 0.918~1.180 SOFA评分 1.801 <0.001 1.424~2.278 1.865 <0.001 1.434~2.424 血乳酸 1.103 0.080 0.988~1.231 — — — 血肌酐 1.001 0.157 0.999~1.003 — — — 尿素氮 1.048 0.013 1.010~1.088 1.279 0.052 1.000~1.083 胱抑素C 1.320 0.072 0.975~1.788 — — — PCT 1.007 0.365 0.992~1.021 — — — BNP 1.000 0.074 1.000~1.001 — — — T2MI发生率 2.594 0.008 0.288~5.225 2.556 0.037 1.060~6.163 -

[1] Reyes LF, Garcia-Gallo E, Pinedo J, et al. Scores to Predict Long-term Mortality in Patients With Severe Pneumonia Still Lacking[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2021, 72(9): e442-e443. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1140

[2] 任轲, 林金锋, 王亚东, 等. 早期不同蛋白补充量对重症肺炎患者预后的影响[J]. 临床急诊杂志, 2023, 24(4): 185-189. https://lcjz.whuhzzs.com/article/doi/10.13201/j.issn.1009-5918.2023.04.003

[3] Sawayama Y, Takashima N, Harada A, et al. Incidence and In-Hospital Mortality of Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Report from a Population-Based Registry in Japan[J]. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2023, 30(10): 1407-1419. doi: 10.5551/jat.63888

[4] Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018) [published correction appears in Circulation][J]. Circulation, 2018, 138(20): e618-e651.

[5] Abdelaziz AS, Kamel MA, Ahmed AI, et al. Chemotherapeutic Potential of Epimedium brevicornum Extract: The cGMP-Specific PDE5 Inhibitor as Anti-Infertility Agent Following Long-Term Administration of Tramadol in Male Rats[J]. Antibiotics (Basel), 2020, 9(6): 318. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9060318

[6] Bularga A, Taggart C, Mendusic F, et al. Assessment of Oxygen Supply-Demand Imbalance and Outcomes Among Patients With Type 2 Myocardial Infarction: A Secondary Analysis of the High-STEACS Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial[J]. JAMA Netw Open, 2022, 5(7): e2220162. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.20162

[7] Adeyemi OS, Shittu EO, Akpor OB, et al. Silver nanoparticles restrict microbial growth by promoting oxidative stress and DNA damage[J]. EXCLI J, 2020, 19: 492-500.

[8] Gouda P, Kay R, Gupta A, et al. Anticoagulation in type 2 myocardial infarctions: Lessons learned from the rivaroxaban in type 2 myocardial infarctions feasibility trial[J]. Contemp Clin Trials Commun, 2023, 33: 101143. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2023.101143

[9] Castaldi G, Bharadwaj AS, Bagur R, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of type 2 myocardial infarction in patients with cancer: A retrospective analysis from the National Inpatient Sample dataset[J]. Int J Cardiol, 2023, 389: 131154. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2023.131154

[10] Sokhal BS, Matetić A, Paul TK, et al. Management and outcomes of patients admitted with type 2 myocardial infarction with and without standard modifiable risk factors[J]. Int J Cardiol, 2023, 371: 391-396. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2022.09.037

[11] Hawatmeh A, Thawabi M, Aggarwal R, et al. Implications of Misclassification of Type 2 Myocardial Infarction on Clinical Outcomes[J]. Cardiovasc Revasc Med, 2020, 21(2): 176-179. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2019.04.009

[12] Reid C, Alturki A, Yan A, et al. Meta-analysis Comparing Outcomes of Type 2 Myocardial Infarction and Type 1 Myocardial Infarction With a Focus on Dual Antiplatelet Therapy[J]. CJC Open, 2020, 2(3): 118-128. doi: 10.1016/j.cjco.2020.02.005

[13] White K, Kinarivala M, Scott I. Diagnostic features, management and prognosis of type 2 myocardial infarction compared to type 1 myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. BMJ Open, 2022, 12(2): e055755. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055755

[14] Martin-Loeches I, Torres A, Nagavci B, et al. ERS/ESICM/ESCMID/ALAT guidelines for the management of severe community-acquired pneumonia[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2023, 49(6): 615-632. doi: 10.1007/s00134-023-07033-8

[15] Wang F, Wu X, Hu SY, et al. Type 2 myocardial infarction among critically ill elderly patients in the Intensive Care Unit: the clinical features and in-hospital prognosis[J]. Aging Clin Exp Res, 2020, 32(9): 1801-1807. doi: 10.1007/s40520-019-01369-2

[16] Zallocco F, Omenetti A, Poletti V, et al. Recurrent pneumonia and severe opportunistic infections in declining immunity and autoimmune manifestations[J]. Pulmonology, 2023, 29(2): 167-169. doi: 10.1016/j.pulmoe.2022.06.004

[17] Qu J, Zhang J, Chen Y, et al. Aetiology of severe community acquired pneumonia in adults identified by combined detection methods: a multi-centre prospective study in China[J]. Emerg Microbes Infect, 2022, 11(1): 556-566. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2022.2035194

[18] Nair GB, Niederman MS. Updates on community acquired pneumonia management in the ICU[J]. Pharmacol Ther, 2021, 217: 107663. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107663

[19] 袁雪梅, 韩小琴, 韦梅, 等. 早期肝素结合蛋白联合降钙素原对重症肺炎患者的预后评估价值[J]. 临床急诊杂志, 2022, 23(8): 553-556. https://lcjz.whuhzzs.com/article/doi/10.13201/j.issn.1009-5918.2022.08.003

[20] 张康, 姬文帅, 孔欣欣, 等. 序贯性脏器功能衰竭评分和CURB-65评分及肺炎严重指数评分对重症肺炎患者28 d死亡的预测效能比较研究[J]. 中国全科医学, 2023, 26(18): 2217-2222, 2226. doi: 10.12114/j.issn.1007-9572.2022.0880

[21] Sekhar S, Pratap V, Gaurav K, et al. The Value of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) Score and Serum Lactate Level in Sepsis and Its Use in Predicting Mortality[J]. Cureus, 2023, 15(7): e42683.

[22] Song Y, Sun W, Dai D, et al. Prediction value of procalcitonin combining CURB-65 for 90-day mortality in community-acquired pneumonia[J]. Expert Rev Respir Med, 2021, 15(5): 689-696. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2021.1865810

[23] Zatz R, De Nucci G. Endothelium-Derived Dopamine and 6-Nitrodopamine in the Cardiovascular System[J]. Physiology (Bethesda), 2024, 39(1): 44-59.

[24] Rubin DS, Lin AZ, Ward RP, et al. Trends and In-Hospital Mortality for Perioperative Myocardial Infarction After the Introduction of a Diagnostic Code for Type 2 Myocardial Infarction in the United States Between 2016 and 2018[J]. Anesth Analg, 2024, 138(2): 420-429. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000006404

[25] Ma SL, Hu SY, Li WL, et al. Correlation between traditional chinese medicine syndromes and type 2 myocardial infarction in critically ill patients with pulmonary disease[J]. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med, 2022, 2022: 9329683.

[26] Jiang GJ, Gao RK, Wang M, et al. A Nomogram Model for Predicting Type-2 Myocardial Infarction Induced by Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding[J]. Curr Med Sci, 2022, 42(2): 317-326.

[27] Šerpytis R, Lizaitis M, Majauskienė E, et al. Type 2 Myocardial Infarction and Long-Term Mortality Risk Factors: A Retrospective Cohort Study[J]. Adv Ther, 2023, 40(5): 2471-2480.

[28] Eggers KM, Baron T, Chapman AR, et al. Management and outcome trends in type 2 myocardial infarction: an investigation from the SWEDEHEART registry[J]. Sci Rep, 2023, 13(1): 7194.

[29] Wereski R, Kimenai DM, Bularga A, et al. Risk factors for type 1 and type 2 myocardial infarction[J]. Eur Heart J, 2022, 43(2): 127-135.

-

下载:

下载: