Association between hemoglobin glycation index and poor prognosis in patients with sepsis

-

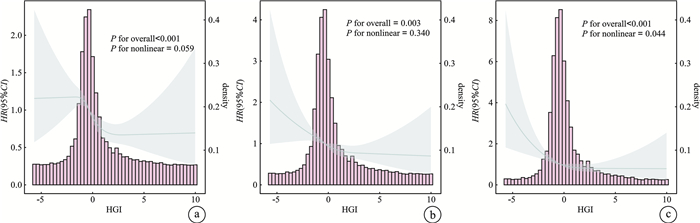

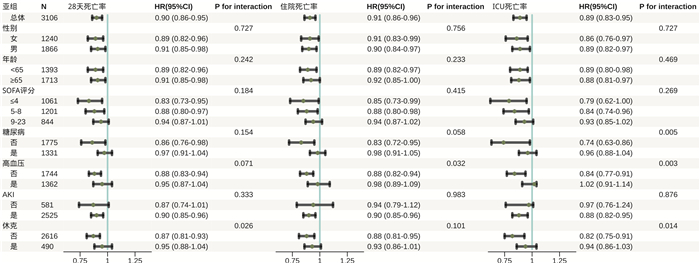

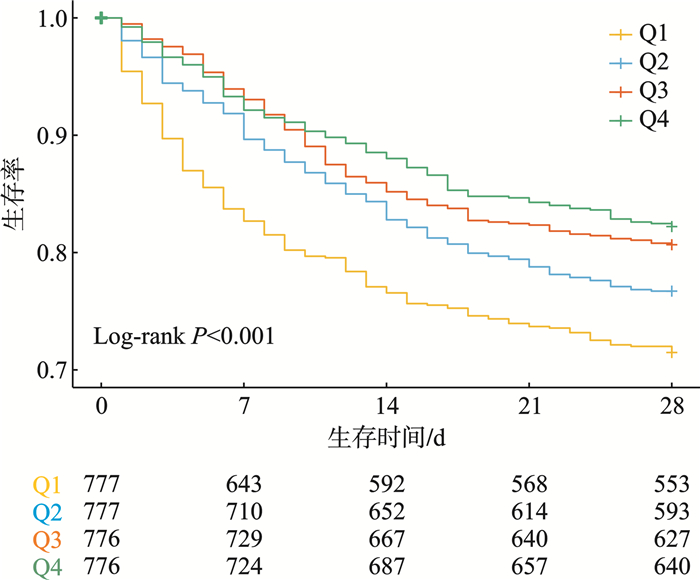

摘要: 目的 探讨血红蛋白糖化指数(hemoglobin glycation index,HGI)对脓毒症患者全因死亡率的预测价值。方法 选取MIMIC-Ⅳ 3.0中符合脓毒症3.0诊断标准首次入住重症监护病房(intensive care unit,ICU)的3 106例成年患者。收集患者的临床资料,基于HGI的四分位数分组(Q1、Q2、Q3和Q4组),绘制K-M生存曲线,并使用log-rank检验比较组间生存状态的差异。采用多因素Cox比例风险回归模型探讨HGI与全因死亡率之间的相关性。通过限制性立方样条回归和亚组分析对结果进行验证,以评估其稳健性。结果 3 106例患者中,ICU 28 d死亡率、住院死亡率和ICU死亡率分别为22.12%、19.96%和14.94%。Kaplan-Meier曲线和log-rank检验显示,Q1组的中位生存时间显著短于其他组(P < 0.01)。多因素Cox比例风险回归分析表明,HGI与脓毒症患者死亡风险显著相关(P < 0.05),即HGI降低与死亡风险增加相关。限制性立方样条回归分析显示,HGI增加使ICU 28 d死亡率和住院死亡率线性下降,ICU死亡率虽非线性下降,但也随HGI增加而降低。不同结局的亚组间效应大小和方向保持一致。结论 HGI低水平与脓毒症患者不良预后显著相关。

-

关键词:

- 脓毒症 /

- 血红蛋白糖化指数 /

- 预后 /

- 重症监护医学信息数据库

Abstract: Objective To investigate the predictive value of the hemoglobin glycation index(HGI) for mortality in sepsis patients.Methods A total of 3 106 adult patients from the MIMIC-Ⅳ 3.0 database met the diagnostic criteria for sepsis 3.0. Clinical data were collected and patients were stratified based on HGI quartiles(Q1, Q2, Q3 and Q4). Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank tests were used to compare survival differences between groups. The association between HGI and mortality was examined using the multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model. The results were validated using RCS regression and subgroup analyses to assess their robustness.Results The 28-day mortality, hospital mortality, and ICU mortality were 22.12%, 19.96% and 14.94%, respectively. Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests indicated that the median survival time for the Q1 group was significantly shorter than that for other groups(P < 0.01). Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis showed that lower HGI was significantly associated with increased mortality risk in sepsis(P < 0.05), indicating that a decrease in HGI was associated with higher mortality risk.RCS analysis revealed that an increase in HGI was associated with a linear decrease in 28-day and hospital mortality, while ICU mortality decreased non-linearly with increasing HGI levels. The effect size and direction of different outcomes remained consistent across subgroups.Conclusion Low HGI is significantly associated with poor prognosis in sepsis.-

Key words:

- sepsis /

- hemoglobin glycation index /

- prognosis /

- MIMIC-IV

-

-

表 1 不同血红蛋白糖化指数组间的临床特征比较M(P25,P75)

指标 Q1(≤-0.861) Q2(-0.861,-0.337) Q3(-0.337,0.367) Q4(>0.367) P 男/例(%) 457(58.82) 485(62.42) 459(59.15) 465(59.92) 0.460 年龄/岁 63.57(51.39,73.40) 67.41(55.45,77.63) 70.68(60.23,78.81) 66.06(55.85,74.54) < 0.001 体重/kg 77.9(67.3,94.0) 80.0(68.8,95.7) 83.3(69.5,100.0) 85.5(72.0,103.0) < 0.001 生命体征 心率/(次/min) 91(78,106) 86(73,100) 85(73,100) 89(76,102) < 0.001 收缩压/mmHg 123(105,142) 127(108,143) 128(111,146) 128(111,147) < 0.001 实验室检查 WBC/(×109/L) 13.8(9.5,19.0) 11.3(8.3,15.5) 10.4(8.0,14.7) 11.4(8.3,16.1) < 0.001 PLT/(×109/L) 210(152,278) 210(157,281) 212(160,274) 225(169,288) 0.006 Hb/(g/dL) 11.9(9.9,13.8) 12.1(10.5,13.8) 12.3(10.5,13.6) 11.9(10.1,13.4) 0.040 RDW/% 14.0(13.2,15.8) 13.9(13.1,15.1) 14.2(13.3,15.5) 14.1(13.2,15.5) 0.003 ALT/(IU/L) 39.0(21.0,82.7) 30.0(18.0,58.0) 30.0(17.5,51.0) 31.0(20.0,51.0) < 0.001 AST/(IU/L) 62.4(33.0,128.5) 47.0(26.0,87.0) 41.0(24.5,79.5) 44.8(25.0,82.5) < 0.001 ALP/(IU/L) 86.0(67.0,115.0) 81.0(64.0,98.0) 84.0(66.0,105.8) 91.0(75.0,119.9) < 0.001 TB/(mg/dL) 0.7(0.5,1.1) 0.7(0.5,0.9) 0.6(0.5,0.9) 0.6(0.4,0.8) < 0.001 BUN/(mg/dL) 20(14,34) 19(14,31) 21(15,30) 23(15,40) < 0.001 SCr/(mg/dL) 1.2(0.9,1.8) 1.0(0.8,1.5) 1.0(0.8,1.4) 1.2(0.8,1.9) < 0.001 PT/s 13.3(11.9,15.9) 13.0(11.9,15.2) 13.4(12.1,15.7) 13.1(11.9,15.1) 0.016 PTT/s 30.7(26.8,39.9) 30.2(26.4,38.3) 30.2(26.6,37.5) 29.6(26.4,35.4) 0.007 AG/(mEq/L) 17(14,21) 15(13,17) 15(13,17) 16(13,19) < 0.001 钠/(mEq/L) 138(135,140) 138(136,141) 139(136,141) 137(134,140) < 0.001 钾/(mEq/L) 4.3(3.9,4.8) 4.2(3.8,4.6) 4.2(3.9,4.6) 4.3(3.9,4.9) < 0.001 氯/(mEq/L) 102(98,105) 103(99,106) 103(99,105) 101(97,105) < 0.001 HbA1c/% 5.3(5.0,5.7) 5.6(5.4,5.8) 6.1(5.8,6.4) 8.4(7.2,10.4) < 0.001 FPG/(mg/dL) 183(134,272) 130(109,160) 126(104,162) 192(140,301) < 0.001 HGI/% -1.24(-1.63,-1.01) -0.58(-0.71,-0.46) -0.06(-0.22,0.14) 1.47(0.74,2.82) < 0.001 疾病严重程度评分/分 SOFA 7(5,10) 6(4,9) 5(3,8) 6(4,8) < 0.001 CCI 6(4,8) 6(4,8) 6(5,8) 7(5,9) < 0.001 SAPS Ⅱ 39(32,50) 37(29,45) 35(29,43) 38(30,46) < 0.001 APS Ⅲ 59(44,83) 52(38,72) 48(36,67) 55(42,74) < 0.001 合并症/例(%) 肾脏疾病 158(20.33) 151(19.43) 166(21.39) 239(30.80) < 0.001 恶性肿瘤 60(7.72) 50(6.44) 51(6.57) 58(7.47) 0.690 充血性心力衰竭 244(31.40) 252(32.43) 323(41.62) 306(39.43) < 0.001 糖尿病 204(26.25) 170(21.88) 265(34.15) 692(89.18) < 0.001 高血压 297(38.22) 363(46.72) 363(46.78) 339(43.69) 0.002 脑卒中 204(26.25) 233(29.99) 234(30.15) 190(24.48) 0.027 肺炎 248(31.92) 254(32.69) 275(35.44) 275(35.44) 0.320 休克 144(18.53) 107(13.77) 95(12.24) 144(18.56) < 0.001 慢性阻塞性肺疾病 80(10.30) 68(8.75) 89(11.47) 78(10.05) 0.370 冠心病 248(31.92) 230(29.60) 216(27.84) 260(33.51) 0.077 房颤 219(28.19) 273(35.14) 333(42.91) 221(28.48) < 0.001 肝病 113(14.54) 55(7.08) 48(6.19) 37(4.77) < 0.001 急性肾衰竭 635(81.72) 619(79.67) 644(82.99) 627(80.80) 0.390 感染部位/例(%) 肺部感染 158(20.33) 160(20.59) 168(21.65) 149(19.20) 0.690 消化系感染 53(6.82) 31(3.99) 35(4.51) 40(5.15) 0.064 泌尿系感染 146(18.79) 140(18.02) 166(21.39) 168(21.65) 0.180 其他感染 328(42.21) 270(34.75) 264(34.02) 336(43.30) < 0.001 糖皮质激素/例(%) 20(2.57) 19(2.45) 20(2.58) 25(3.22) 0.780 注:1 mmHg=0.133 kPa。 表 2 不同血红蛋白糖化指数组间不良事件及临床预后对比

M(P25,P75) 指标 Q1(≤-0.861) Q2(-0.861,-0.337) Q3(-0.337,0.367) Q4(>0.367) P 住院时间/d 14.8(13.3) 15.7(15.3) 15.5(13.5) 17.2(15.9) 0.004 院内死亡/例(%) 200(25.74) 148(19.05) 139(17.91) 133(17.14) < 0.001 ICU停留时间/d 8.3(8.9) 8.5(8.6) 8.1(8.1) 8.6(9.0) 0.870 ICU死亡/例(%) 157(20.21) 115(14.80) 94(12.11) 98(12.63) < 0.001 28 d死亡/例(%) 219(28.19) 180(23.17) 150(19.33) 138(17.78) < 0.001 注:ICU死亡指患者在ICU期间死亡;28 d死亡指患者进入ICU后28 d内发生的死亡事件。 表 3 脓毒症患者全因死亡率的Cox回归分析

暴露 模型1 模型2 模型3 HR(95%CI) P HR(95%CI) P HR(95%CI) P ICU 28 d全因死亡率 HGIa) 0.86(0.82~0.91) < 0.001 0.87(0.82~0.92) < 0.001 0.90(0.86~0.95) < 0.001 Q1b) 1.77(1.43~2.19) < 0.001 1.71(1.38~2.13) < 0.001 1.48(1.18~1.85) 0.001 Q2b) 1.36(1.09~1.70) 0.007 1.26(1.01~1.57) 0.044 1.36(1.08~1.72) 0.009 Q3b) 1.10(0.87~1.38) 0.430 0.99(0.78~1.25) 0.918 1.17(0.92~1.48) 0.199 住院全因死亡率 HGIa) 0.87(0.82~0.92) < 0.001 0.88(0.83~0.93) < 0.001 0.91(0.86~0.96) 0.001 Q1b) 1.72(1.38~2.15) < 0.001 1.68(1.34~2.10) < 0.001 1.41(1.11~1.78) 0.004 Q2b) 1.24(0.98~1.56) 0.078 1.17(0.93~1.49) 0.186 1.17(0.92~1.50) 0.204 Q3b) 1.16(0.92~1.48) 0.215 1.09(0.85~1.38) 0.505 1.16(0.91~1.48) 0.236 ICU全因死亡率 HGIa) 0.86(0.80~0.92) < 0.001 0.86(0.81~0.93) < 0.001 0.89(0.83~0.95) 0.001 Q1b) 1.65(1.28~2.12) < 0.001 1.59(1.23~2.06) < 0.001 1.42(1.09~1.85) 0.010 Q2b) 1.21(0.92~1.59) 0.163 1.17(0.89~1.54) 0.255 1.23(0.92~1.64) 0.157 Q3b) 1.07(0.80~1.42) 0.660 1.01(0.76~1.35) 0.936 1.14(0.85~1.52) 0.397 注:a)HGI作为连续性变量纳入Cox比例风险回归模型;b)HGI作为分类变量纳入Cox比例风险回归模型,以Q4为参考组。模型1:未调整协变量;模型2:调整年龄、性别、体重;模型3:调整年龄、性别、体重、心率、收缩压、SOFA评分、CCI评分及既往糖皮质激素使用情况。 -

[1] Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock(sepsis-3)[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(8): 801-810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287

[2] Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990-2017: analysis for the global burden of disease study[J]. Lancet, 2020, 395(10219): 200-211. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32989-7

[3] Prescott HC, Angus DC. Enhancing recovery from sepsis: a review[J]. JAMA, 2018, 319(1): 62-75. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.17687

[4] He RR, Yue GL, Dong ML, et al. Sepsis biomarkers: advancements and clinical applications-a narrative review[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2024, 25(16): 9010. doi: 10.3390/ijms25169010

[5] Kahn F, Tverring J, Mellhammar L, et al. Heparin-binding protein as a prognostic biomarker of sepsis and disease severity at the emergency department[J]. Shock, 2019, 52(6): e135-e145. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001332

[6] Karakike E, Adami ME, Lada M, et al. Late peaks of HMGB1 and sepsis outcome: evidence for synergy with chronic inflammatory disorders[J]. Shock, 2019, 52(3): 334-339. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001265

[7] Jiang WQ, Li XS, Ding HG, et al. PD-1 in tregs predicts the survival in sepsis patients using sepsis-3 criteria: a prospective, two-stage study[J]. Int Immunopharmacol, 2020, 89(Pt A): 107175. http://www.zhangqiaokeyan.com/journal-foreign-detail/0704028603315.html

[8] Hsiao SY, Kung CT, Tsai NW, et al. Concentration and value of endocan on outcome in adult patients after severe sepsis[J]. Clin Chim Acta, 2018, 483: 275-280. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2018.05.007

[9] Trevelin SC, Carlos D, Beretta M, et al. Diabetes mellitus and sepsis: a challenging association[J]. Shock, 2017, 47(3): 276-287. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000778

[10] Nayak AU, Singh BM, Dunmore SJ. Potential clinical error arising from use of HbA1c in diabetes: effects of the glycation gap[J]. Endocr Rev, 2019, 40(4): 988-999. doi: 10.1210/er.2018-00284

[11] Hempe JM, Gomez R, McCarter RJ Jr, et al. High and low hemoglobin glycation phenotypes in type 1 diabetes: a challenge for interpretation of glycemic control[J]. J Diabetes Complications, 2002, 16(5): 313-320. doi: 10.1016/S1056-8727(01)00227-6

[12] Hempe JM, Liu SQ, Myers L, et al. The hemoglobin glycation index identifies subpopulations with harms or benefits from intensive treatment in the ACCORD trial[J]. Diabetes Care, 2015, 38(6): 1067-1074. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1844

[13] Liu SQ, Hempe JM, McCarter RJ, et al. Association between inflammation and biological variation in hemoglobin A1c in U.S. nondiabetic adults[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2015, 100(6): 2364-2371. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-4454

[14] Lyu L, Yu J, Liu YW, et al. High hemoglobin glycation index is associated with telomere attrition independent of HbA1c, mediated by TNF-α[J]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2022, 107(2): 462-473. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab703

[15] Lin ZY, He JN, Yuan S, et al. Hemoglobin glycation index and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with diabetes and coronary artery disease: insights from a large cohort study[J]. Nutr Diabetes, 2024, 14(1): 69. doi: 10.1038/s41387-024-00318-x

[16] Huang Y, Huang XT, Zhong LY, et al. Glycated haemoglobin index is a new predictor for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in the adults[J]. Sci Rep, 2024, 14(1): 19629. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-70666-2

[17] Wei X, Chen XH, Zhang ZP, et al. Risk analysis of the association between different hemoglobin glycation index and poor prognosis in critical patients with coronary heart disease-a study based on the MIMIC-Ⅳ database[J]. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2024, 23(1): 113. doi: 10.1186/s12933-024-02206-1

[18] Wang SH, Song SN, Gao JX, et al. Glycated haemoglobin variability and risk of renal function declinein type 2 diabetes mellitus: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Diabetes Obesity Metabolism, 2024, 26(11): 5167-5182. doi: 10.1111/dom.15861

[19] Johnson AEW, Bulgarelli L, Shen L, et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset[J]. Sci Data, 2023, 10(1): 1. doi: 10.1038/s41597-022-01899-x

[20] 潘岳松, 金奥铭, 王梦星. 临床研究样本量的估计方法和常见错误[J]. 中国卒中杂志, 2022, 17(1): 31-35.

[21] He AF, Liu JL, Qiu JX, et al. Risk and mediation analyses of hemoglobin glycation index and survival prognosis in patients with sepsis[J]. Clin Exp Med, 2024, 24(1): 183. doi: 10.1007/s10238-024-01450-9

[22] Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury[J]. Nephron Clin Pract, 2012, 120(4): c179-c184. doi: 10.1159/000339789

[23] Zheng R, Qian SZ, Shi YY, et al. Association between triglyceride-glucose index and in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis: analysis of the MIMIC-Ⅳ database[J]. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2023, 22(1): 307. doi: 10.1186/s12933-023-02041-w

[24] Hu WH, Chen H, Ma CC, et al. Identification of indications for albumin administration in septic patients with liver cirrhosis[J]. Crit Care, 2023, 27(1): 300. doi: 10.1186/s13054-023-04587-3

[25] Yan FJ, Chen XH, Quan XQ, et al. Association between the stress hyperglycemia ratio and 28-day all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis: a retrospective cohort study and predictive model establishment based on machine learning[J]. Cardiovasc Diabetol, 2024, 23(1): 163. doi: 10.1186/s12933-024-02265-4

[26] 齐霜, 周飞虎. 电子病历数据库脓毒症病例筛选方法综述[J]. 解放军医学院学报, 2020, 41(9): 918-921, 929.

[27] Wang M, Li S, Zhang X, et al. Association between hemoglobin glycation index and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the patients with type2 diabetes mellitus[J]. J Diabetes Investig, 2023, 14(11): 1303-1311. doi: 10.1111/jdi.14066

[28] Xing Y, Zhen Y, Yang L, et al. Association between hemoglobin glycation index and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease[J]. Front Endocrinol(Lausanne), 2023, 14: 1094101. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1094101

[29] Dungan KM, Braithwaite SS, Preiser JC. Stress hyperglycaemia[J]. Lancet, 2009, 373(9677): 1798-1807. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60553-5

[30] Fowler C, Raoof N, Pastores SM. Sepsis and adrenal insufficiency[J]. J Intensive Care Med, 2023, 38(11): 987-996. doi: 10.1177/08850666231183396

[31] Vedantam D, Poman DS, Motwani L, et al. Stress-induced hyperglycemia: consequences and management[J]. Cureus, 2022, 14(7): e26714.

[32] van Vught LA, Wiewel MA, Klein Klouwenberg PM, et al. Admission hyperglycemia in critically ill sepsis patients: association with outcome and host response[J]. Crit Care Med, 2016, 44(7): 1338-1346. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001650

[33] Zohar Y, Zilberman Itskovich S, Koren S, et al. The association of diabetes and hyperglycemia with sepsis outcomes: a population-based cohort analysis[J]. Intern Emerg Med, 2021, 16(3): 719-728. doi: 10.1007/s11739-020-02507-9

[34] Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021[J]. Crit Care Med, 2021, 49(11): e1063-e1143. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005337

[35] Esposito K, Nappo F, Marfella R, et al. Inflammatory cytokine concentrations are acutely increased by hyperglycemia in humans: role of oxidative stress[J]. Circulation, 2002, 106(16): 2067-2072. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000034509.14906.AE

[36] Krogh-Madsen R, Møller K, Dela F, et al. Effect of hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia on the response of IL-6, TNF-alpha, and FFAs to low-dose endotoxemia in humans[J]. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2004, 286(5): E766-E772. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00468.2003

[37] Zhou XM, Liu C, Xu Z, et al. Combining host immune response biomarkers and clinical scores for early prediction of sepsis in infection patients[J]. Ann Med, 2024, 56(1): 2396569. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2024.2396569

[38] Yu W, Zeng LY, Lian X, et al. Dynamic cytokine profiles of bloodstream infection caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae in China[J]. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob, 2024, 23(1): 79. doi: 10.1186/s12941-024-00739-7

[39] Feng Y, Luo S, Fang C, et al. ANGPTL8 deficiency attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced liver injury by improving lipid metabolic dysregulation[J]. J Lipid Res, 2024, 65(8): 100595. doi: 10.1016/j.jlr.2024.100595

[40] Kinoshita K, Kraydieh S, Alonso O, et al. Effect of posttraumatic hyperglycemia on contusion volume and neutrophil accumulation after moderate fluid-percussion brain injury in rats[J]. J Neurotrauma, 2002, 19(6): 681-692. doi: 10.1089/08977150260139075

[41] Ceriello A, Quagliaro L, Piconi L, et al. Effect of postprandial hypertriglyceridemia and hyperglycemia on circulating adhesion molecules and oxidative stress generation and the possible role of simvastatin treatment[J]. Diabetes, 2004, 53(3): 701-710. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.3.701

[42] Altannavch TS, Roubalová K, Kucera P, et al. Effect of high glucose concentrations on expression of ELAM-1, VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 in HUVEC with and without cytokine activation[J]. Physiol Res, 2004, 53(1): 77-82. http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Katerina_Roubalova/publication/6363572_Effect_of_high_glucose_concentrations_on_expression_of_ELAM-1_VCAM-1_and_ICAM-1_in_HUVEC_with_and_without_cytokine_activation/links/09e4150ed20fedbd1b000000

[43] Zhao M, Wang ST, Zuo AN, et al. HIF-1α/JMJD1A signaling regulates inflammation and oxidative stress following hyperglycemia and hypoxia-induced vascular cell injury[J]. Cell Mol Biol Lett, 2021, 26(1): 40. doi: 10.1186/s11658-021-00283-8

-

计量

- 文章访问数: 319

- 施引文献: 0

下载:

下载: