MIMIC-Ⅲ-based analysis of clinical characteristics and prognostic correlation in patients with sepsis

-

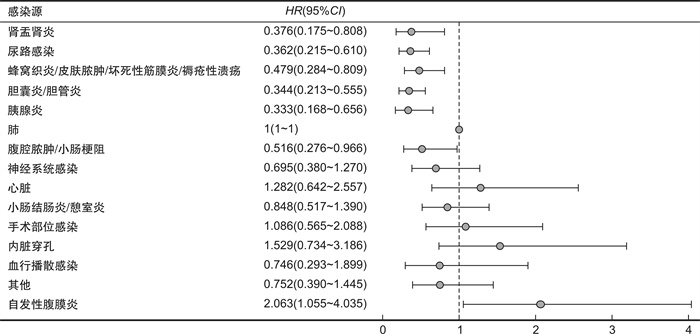

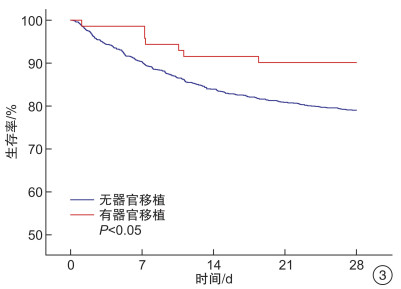

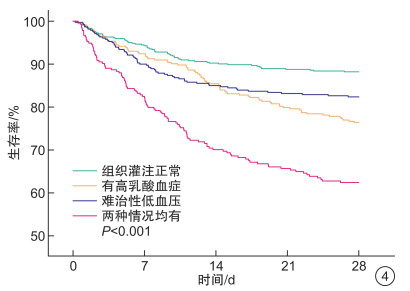

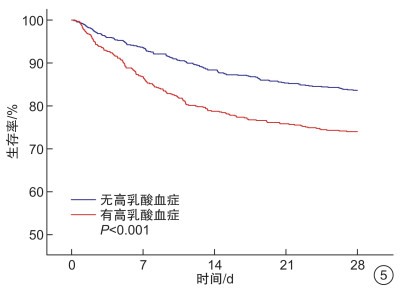

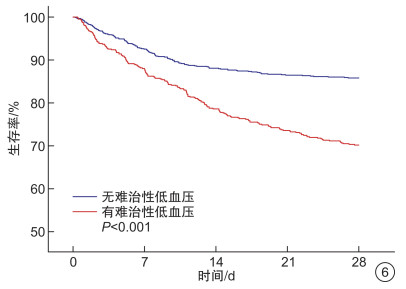

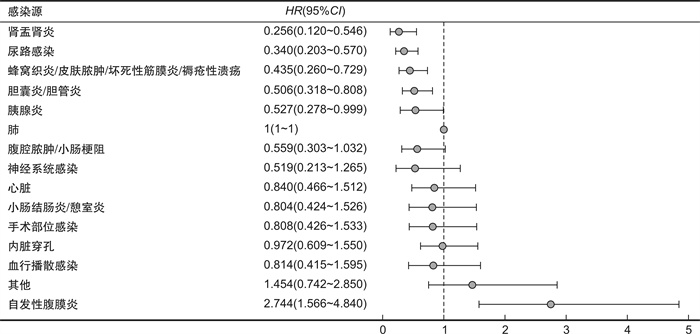

摘要: 目的 分析不同感染解剖来源、组织灌注和免疫状态的脓毒症患者的预后差异并探讨其与预后相关性。方法 回顾性分析重症监护医学信息数据库(MIMIC-Ⅲ)中首次入住ICU的成人(≥18岁)初诊脓毒症患者的病历信息。共纳入1540例患者,根据脓毒症患者不同感染解剖来源、组织灌注和免疫状态将其分为不同亚组,采用多因素Cox回归分析,以确定不同感染解剖来源28 d病死率之间的相关性。采用Kaplan-Meier生存曲线,以显示不同免疫状态和组织灌注状态脓毒症患者28 d病死率。结果 ① 纳入研究的脓毒症患者28 d总体病死率为20.5%,自发性腹膜炎病死率最高(61.9%),其次是肺、内脏穿孔,病死率分别为26.4%、25.6%,肾盂肾炎病死率最低(7.7%),不同感染解剖来源病死率差异有统计学意义(P < 0.01),且校正差异仍有统计学意义(P < 0.01)。②在纳入的免疫状态标准中[实体器官移植(SOT)、造血干细胞移植、糖皮质激素等],仅SOT差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05),SOT与非SOT脓毒症患者病死率分别为9.9%和21.0%。③难治性低血压的脓毒症患者病死率为29.8%,无难治性低血压者病死率为14.2%,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.01);高乳酸血症的脓毒症患者病死率为26.0%,非高乳酸血症的脓毒症患者为16.1%(P < 0.01)。结论 不同感染解剖来源的脓毒症预后存在差异,组织灌注差提示更高的脓毒症病死率,而接受SOT的脓毒症患者病死率更低。脓毒症临床分型可减少异质性对脓毒症临床预后判断的影响,有助于提升其临床精准医疗和科学研究。Abstract: Objective To analyze the prognostic differences and explore their relevance to the prognosis of sepsis patients with different anatomical sources of infection, tissue perfusion, and immune status.Methods The medical records of adult(≥18 years old) patients with primary sepsis who were admitted to the ICU for the first time in the Medical Information in Intensive Care database(MIMIC-Ⅲ) were retrospectively analyzed. A total of 1540 patients were included, and sepsis patients were divided into subgroups according to their different anatomical sources of infection, tissue perfusion, and immune status, and multifactorial Cox regression analysis was used to determine the correlation between 28-day mortality rates for different anatomical sources of infection. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to show 28-day mortality in sepsis patients with different immune statuses and tissue perfusion statuses.Results ① The overall 28-day mortality rate for sepsis patients included in the study was 20.5%. Spontaneous peritonitis had the highest mortality rate of 61.9%, followed by pulmonary and visceral perforation with 26.4% and 25.6%, respectively, and pyelonephritis had the lowest mortality rate(7.7%). The differences in mortality rates between anatomical sources of infection were significant(P < 0.01), no matter corrected or uncorrected. ②Of the included immune status criteria[solid organ transplantation(SOT), hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, glucocorticoids, etc.], only SOT was statistically significant(P < 0.05), with mortality rates of 9.9% and 21.0% for SOT and non-SOT sepsis patients respectively. ③The mortality rate was 29.8% in sepsis patients with refractory hypotension and 14.2% in those without refractory hypotension(P < 0.01); the mortality rate was 26.0% in sepsis patients with hyperlactatemia and 16.1% in sepsis patients without hyperlactatemia(P < 0.01).Conclusion The prognosis of sepsis differs between anatomical sources of infection, and poor tissue perfusion correlates with higher mortality while SOT suggests lower mortality. sepsis clinical typing can reduce the impact of sepsis heterogeneity on the accuracy of prognosis judgment and improve the related precision medicine and scientific research.

-

Key words:

- sepsis /

- heterogeneity /

- source of infection /

- immune status /

- mortality /

- MIMIC-Ⅲ

-

-

表 1 人口统计学基线特征

M(Q1,Q3) 指标 所有患者(n=1540) 生存组(n=1225) 死亡组(n=315) P 年龄/岁 69.8(56.8,81.7) 68.6(55.5,80.6) 74.7(63.1,83.5) < 0.001 男性/例(%) 849(55.1) 667(54.4) 182(57.8) 0.319 白种人/例(%) 1129(73.3) 906(74.0) 223(70.8) < 0.05 基础生命体征 心率/(次·min-1) 91.0(79.3,103.0) 90.3(78.4,102.8) 94.4(83.1,104.9) 0.002 平均动脉压/mmHg 71.6(66.4,77.5) 71.9(66.7,77.7) 70.0(64.8,76.6) < 0.001 呼吸/(次·min-1) 20.8(18.0,24.1) 20.7(17.9,23.7) 21.3(18.4,25.3) 0.003 体温/℃ 36.9(36.5,37.4) 36.9(36.5,37.5) 36.7(36.2,37.1) < 0.001 氧饱和度/% 97.0(95.7,98.4) 97.0(95.7,98.3) 96.9(95.2,98.4) 0.099 实验室检查 血红蛋白(g/dL) 11.0(9.9,12.5) 11.0(9.9,12.5) 11.0(10.0,12.3) 0.856 白细胞(103/μL) 15.0(10.2,21.7) 15.0(10.6,21.3) 15.2(9.1,23.6) 0.749 血小板(103/μL) 229.0(157.0,326.0) 234.0(162.0,326.0) 201.0(126.0,324.0) 0.001 血清钠(mEq/L) 140.0(137.0,143.0) 140.0(137.0,143.0) 140.0(137.0,144.0) 0.603 血清钾(mEq/L) 4.4(4.0,5.0) 4.3(4.0,4.8) 4.7(4.2,5.3) < 0.001 血清肌酐(mg/dL) 1.4(0.9,2.3) 1.3(0.9,2.1) 1.8(1.1,2.9) < 0.001 尿素氮(mg/dL) 29.0(19.0,47.0) 27.0(17.0,43.0) 38.0(25.0,58.5) < 0.001 血糖(mg/dL) 148.0(120.8,198.0) 145.0(120.0,195.0) 157.0(124.0,205.0) 0.008 合并症/例(%) 充血性心力衰竭 510(33.1) 374(30.5) 136(43.2) < 0.001 急性肾功能损伤 834(54.2) 612(50.0) 222(70.5) < 0.001 ARDS 103(6.7) 73(6.0) 30(9.5) 0.033 治疗/例(%) 连续性肾脏替代治疗 72(4.7) 39(3.2) 33(10.5) < 0.001 ICU严重程度评分 SAPS Ⅱ 42.0(33.0,52.0) 40.0(31.0,49.0) 52.0(42.0,62.0) < 0.001 SOFA 6.0(3.0,8.0) 5.0(3.0,8.0) 8.0(5.0,11.0) < 0.001 表 2 感染解剖来源的种类及临床特点

M(Q1,Q3) 感染解剖来源或相关疾病 例(%) 年龄/岁 28 d死亡 SOFA SAPSⅡ 所有患者 1540 68±16 315(20.5) 6(3,8) 42(33,52) 肺脏感染 556(36.1) 70±16 147(26.4) 6(3,8) 43(34,53) 尿路感染 159(10.3) 73±14 16(10.0) 5(3,7) 42(34,50) 胆囊炎/胆管炎 137(8.9) 75±14 20(14.6) 7(5,9) 44(36.5,55) 蜂窝织炎/皮肤脓肿/坏死性筋膜炎/褥疮性溃疡 125(8.1) 64±16 16(12.8) 4(3,7) 37(29,47) 肾盂肾炎 91(5.9) 66±19 7(7.7) 3(2,5) 33(23,45) 内脏穿孔 78(5.1) 64±17 20(25.6) 7(5,10) 45.5(36,54) 腹腔脓肿/小肠梗阻 68(4.4) 66±15 11(16.2) 5(3,8) 45(34.5,55) 胰腺炎 65(4.2) 65±15 10(15.4) 7(5,10) 45(31,54) 心脏 52(3.4) 64±19 12(23.1) 6(3.5,8) 40.5(29.5,50.5) 小肠结肠炎/憩室炎 46(3.0) 69±16 10(21.7) 4(3,7) 38(31,48) 手术部位感染 44(2.9) 63±15 10(22.7) 6(3,8) 40(29.5,54) 血行感染 39(2.5) 62±12 9(23.1) 6(3,9) 39(31,46) 神经系统感染 34(2.2) 63±15 5(14.7) 6(4,7) 35.5(24,46) 其他 25(1.6) 68±17 9(36.0) 6(4,11) 46(38,58) 自发性腹膜炎 21(1.4) 59±13 13(61.9) 10(8,12) 52(36,61) -

[1] Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock(sepsis-3)[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(8): 801-810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287

[2] Shankar-Hari M, Phillips GS, Levy ML, et al. Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock: for the third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock(sepsis-3)[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(8): 775-787. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0289

[3] Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990-2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study[J]. Lancet, 2020, 395(10219): 200-211. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32989-7

[4] 黄昆鹏, 张进祥. 脓毒症的定义、诊断与早期干预: 不可分割的三要素[J]. 临床急诊杂志, 2021, 22(3): 221-226. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-ZZLC202103016.htm

[5] Marshall JC. Why have clinical trials in sepsis failed?[J]. Trends Mol Med, 2014, 20(4): 195-203. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.01.007

[6] Kalil AC, Sweeney DA. Should we manage all septic patients based on a single definition?an alternative approach[J]. Crit Care Med, 2018, 46(2): 177-180. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002778

[7] DeMerle KM, Angus DC, Baillie JK, et al. Sepsis subclasses: a framework for development and interpretation[J]. Crit Care Med, 2021, 49(5): 748-759. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004842

[8] Rogers P, Wang D, Lu ZY. Medical information mart for intensive care: a foundation for the fusion of artificial intelligence and real-world data[J]. Front Artif Intell, 2021, 4: 691626. doi: 10.3389/frai.2021.691626

[9] Salomão R, Ferreira BL, Salomão MC, et al. Sepsis: evolving concepts and challenges[J]. Braz J Med Biol Res, 2019, 52(4): e8595. doi: 10.1590/1414-431x20198595

[10] Dhooria S, Sehgal IS, Agarwal R. Early, goal-directed therapy for septic shock-A patient-level meta-analysis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2017, 377(10): 995.

[11] Hotchkiss RS, ,et al. Immunosuppression in sepsis: a novel understanding of the disorder and a new therapeutic approach[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2013, 13(3): 260-268. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70001-X

[12] 王仲, 魏捷, 朱华栋, 等. 中国脓毒症早期预防与阻断急诊专家共识[J]. 临床急诊杂志, 2020, 21(7): 517-529. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-ZZLC202007001.htm

[13] Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2017, 43(3): 304-377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6

[14] Chou EH, Mann S, Hsu TC, et al. Incidence, trends, and outcomes of infection sites among hospitalizations of sepsis: a nationwide study[J]. PLoS One, 2020, 15(1): e0227752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227752

[15] Chen YS, Liao TY, Hsu TC, et al. Temporal trend and survival impact of infection source among patients with sepsis: a nationwide study[J]. Crit Care Resusc, 2020, 22(2): 126-132.

[16] 何雪梅, 薄禄龙, 姜春玲. 脓毒症免疫抑制与免疫刺激治疗的研究进展[J]. 中华危重病急救医学, 2018, 30(12): 1202-1205. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-4352.2018.12.020

[17] Donnelly JP, Locke JE, MacLennan PA, et al. Inpatient mortality among solid organ transplant recipients hospitalized for sepsis and severe sepsis[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2016, 63(2): 186-194. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw295

[18] Kalil AC, Opal SM. Sepsis in the severely immunocompromised patient[J]. Curr Infect Dis Rep, 2015, 17(6): 32. doi: 10.1007/s11908-015-0487-4

[19] Kalil AC, Syed A, Rupp ME, et al. Is bacteremic sepsis associated with higher mortality in transplant recipients than in nontransplant patients? A matched case-control propensity-adjusted study[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2014, 60(2): 216-222.

[20] Kalil AC, Johnson DW, Lisco SJ, et al. Early goal-directed therapy for sepsis: a novel solution for discordant survival outcomes in clinical trials[J]. Crit Care Med, 2017, 45(4): 607-614. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002235

[21] Kellum JA, Pike F, Yealy DM, et al. Relationship between alternative resuscitation strategies, host response and injury biomarkers, and outcome in septic shock: analysis of the protocol-based care for early septic shock study[J]. Crit Care Med, 2017, 45(3): 438-445. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002206

[22] Group SCCT. Incidence of severe sepsis and septic shock in German intensive care units: the prospective, multicentre INSEP study[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2016, 42(12): 1980-1989. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4504-3

[23] Cecconi M, Evans L, Levy M, et al. Sepsis and septic shock[J]. Lancet, 2018, 392(10141): 75-87.

[24] Seymour CW, Kennedy JN, Wang S, et al. Derivation, validation, and potential treatment implications of novel clinical phenotypes for sepsis[J]. JAMA, 2019, 321(20): 2003-2017.

[25] Iwashyna TJ, Angus DC. Declining case fatality rates for severe sepsis: good data bring good news with ambiguous implications[J]. JAMA, 2014, 311(13): 1295-1297. http://www.ccm.pitt.edu/sites/default/files/ebm/jama_editorial.pdf

-

下载:

下载: