A study on the efficacy of early individualized liquid resuscitation strategy based on P(cv-a) CO2 and lactate clearance rate in patients with septic shock

-

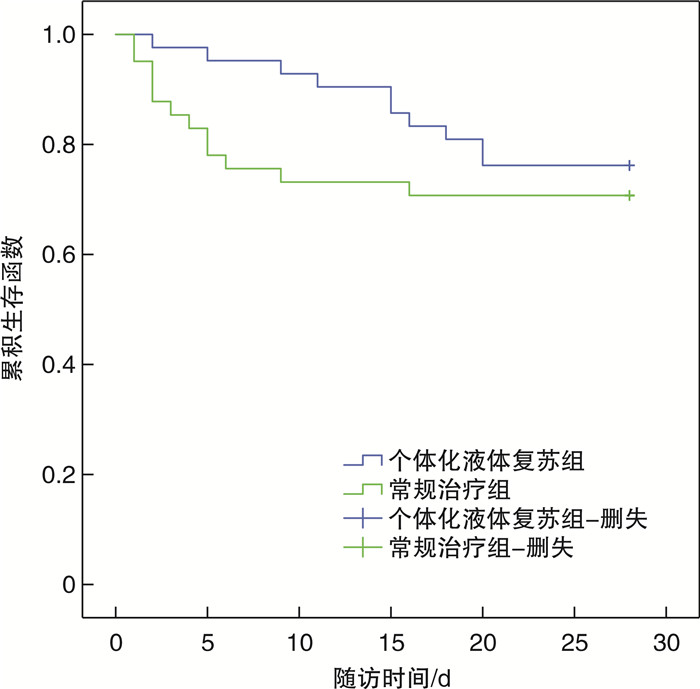

摘要: 目的 研究基于中心静脉-动脉血二氧化碳分压差[P(cv-a)CO2]及乳酸清除率的24 h内个体化液体复苏策略对脓毒性休克患者的疗效。方法 对2021年7月—2023年6月入住南通大学附属常熟医院ICU治疗的83例脓毒性休克患者进行前瞻性研究。根据初始液体复苏3 h后不同液体复苏治疗方案分为个体化液体复苏组及常规治疗组。比较两组心率、平均动脉压、乳酸、P(cv-a)CO2、SOFA评分、APACHE Ⅱ评分、去甲肾上腺素用量、住ICU天数、住院天数等参数的差异,通过Kaplan-Meier生存曲线描述两组患者28 d生存率,使用log-rank检验比较组间生存率的差异。结果 两组患者入组时心率、平均动脉压、初始乳酸值差异无统计学意义,24 h的补液量个体化液体复苏组稍低于常规治疗组,个体化液体复苏组APACHE Ⅱ评分的改善值高于常规治疗组,两组28 d生存率无显著差异。结论 在脓毒性休克患者液体复苏早期使用基于P(cv-a)CO2及乳酸清除率的个体化液体复苏策略可减少不必要的液体输注,更好地改善脓毒性休克患者的器官功能障碍,在复苏早期对两者的监测可用于指导脓毒性休克的治疗。

-

关键词:

- 脓毒性休克 /

- 中心静脉-动脉血二氧化碳分压差 /

- 乳酸清除率 /

- 液体复苏

Abstract: Objective To investigate the efficacy of individualized liquid resuscitation strategy based on central venous-arterial carbon dioxide difference (P[cv-a]CO2) and lactate clearance rate in patients with septic shock.Methods A prospective study was conducted on 83 patients with septic shock admitted to our ICU for treatment from July 2021 to June 2023. Pstients were divided into individualized liquid resuscitation group and conventional treatment group according to different liquid resuscitation treatment plans after 3 hours of initial liquid resuscitation. The differences in parameters such as heart rate, mean arterial pressure, lactate, P(cv-a) CO2, SOFA score, APACHE Ⅱ score, norepinephrine dosage, ICU stay, and hospital stay were compared between two groups were compared. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to describe the 28-day survival rate of the two groups of patients, and the log-rank tests were used to compare the differences in survival rates between groups.Results There was no statistical differences in heart rate, mean arterial pressure, and initial lactate levels between the two groups of patients upon admission. The individualized fluid resuscitation group had slightly lower 24-hour infusion volume than the conventional treatment group. The reduction in APACHE Ⅱ score in the individualized fluid resuscitation group was higher than that in the conventional treatment group, and there was no significant statistical difference in the 28-day survival rate of the two groups.Conclusion Early use of individualized fluid resuscitation strategies based on P(cv-a) CO2 and lactate clearance rate in septic shock patients can lead to less fluid and lower incidence of organ dysfunction. Monitoring both in the early stages of resuscitation can be used to guide the treatment of septic shock. -

-

表 1 两组患者一般资料比较

项目 个体化液体复苏组(42例) 常规治疗组(41例) t/Z/χ2 P 男/女/例 20/22 27/14 2.809 0.094 年龄/岁 72.02±11.876 72.93±10.687 -0.364 0.717 感染部位/例 0.250 0.969 呼吸道 18 17 消化道 15 15 泌尿道 4 3 其他 5 6 体温/℃ 37.72±1.600 37.28±1.534 1.302 0.197 WBC/(×109/L) 14.81±7.77 14.60±10.44 0.078 0.938 PCT/(ng/mL) 19.55(2.93,53.05) 9.80(2.15,33.25) -1.404 0.160 CRP/(mg/L) 112.73±73.13 111.28±87.10 1.129 0.223 T0 Lac/(mmol/L) 4.32(3.15.6.66) 3.90(1.81,6.95) -1.039 0.299 注:T0,入组时。 表 2 两组患者治疗24 h内情况比较

项目 个体化液体复苏组(42例) 常规治疗组(41例) t/Z P T0心率/(次/min) 118.02±23.70 119.02±25.49 -0.185 0.853 T6心率/(次/min) 95.86±18.01 97.27±19.62 -0.341 0.734 T24心率/(次/min) 90.40±18.92 92.46±19.63 -0.487 0.628 T0 MAP/mmHg 63.83±15.32 64.73±9.87 -0.317 0.752 T6 MAP/mmHg 81.63±15.74 81.67±11.88 -0.013 0.990 T24 MAP/mmHg 84.08±13.88 84.78±10.50 -0.259 0.796 T6 LC/% 34.00(6.81,63.02) 10.64(-12.35,37.73) -2.650 0.0081) T24 LC/% 53.40(33.72,72.02) 35.67(9.23,64.68) -2.341 0.0191) T0 gap/mmHg 8.34±3.62 8.81±2.55 -0.688 0.494 T6 gap/mmHg 4.00±3.46 5.86±1.68 -3.129 0.0031) T24 gap/mmHg 4.38±3.82 5.30±2.68 -1.269 0.208 T6补液量/mL 2 416.67±1 005.17 2 247.56±1 062.06 0.745 0.458 T24补液量/mL 4 916.67±1 504.05 5 537.32±1 515.33 -0.873 0.065 注:两组比较,1)P<0.05;T0:入院时;T6:入组6 h;T24:入组24 h;LC:乳酸清除率;gap:中心静脉-动脉血二氧化碳分压差。 表 3 两组患者治疗后疾病严重程度及住院时间的比较

项目 个体化液体复苏组(42例) 常规治疗组(41例) t/Z P D1 SOFA/分 9.14±3.91 9.12±3.89 0.024 0.981 D2 SOFA/分 7.67±4.53 8.32±5.05 -0.618 0.538 ΔSOFA/分 1.5(0.00,3.00) 1.0(-1.00,2.50) -1.000 0.317 D1 APACHE Ⅱ/分 20.98±7.30 20.49±7.63 0.298 0.766 D2 APACHE Ⅱ/分 12.33±5.90 14.39±7.59 -1.380 0.171 ΔAPACHE Ⅱ/分 8.64±4.45 6.10±6.86 2.011 0.0481) 去甲肾最大剂量/(μg/kg/min) 0.22(0.09,0.43) 0.22(0.00,0.59) -0.418 0.676 住ICU天数/d 8.36±5.89 6.97±6.13 1.050 0.297 住院天数/d 14.02±8.87 16.15±13.60 -0.843 0.402 两组比较,1)P<0.05;ΔSOFA:第1天SOFA评分与第2天SOFA评分差值;ΔAPACHE Ⅱ:第1天APACHE Ⅱ评分与第2天APACHE Ⅱ评分差值。 -

[1] Hu B, Chen JCY, Dong Y, et al. Effect of initial infusion rates of fluid resuscitation on outcomes in patients with septic shock: a historical cohort study[J]. Crit Care, 2020, 24(1): 137. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2819-5

[2] Jackson KE, Wang L, Casey JD, et al. Effect of early balanced crystalloids before ICU admission on sepsis outcomes[J]. Chest, 2021, 159(2): 585-595. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.08.2068

[3] Semler MW, Janz DR, Casey JD, et al. Conservative fluid management after sepsis resuscitation: a pilot randomized trial[J]. J Intensive Care Med, 2020, 35(12): 1374-1382. doi: 10.1177/0885066618823183

[4] Kashani K, Kennedy CC, Gajic O. Fluid balance in different phases of resuscitation[J]. J Crit Care, 2020, 60: 350. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.09.005

[5] Mohamed MFH, Malewicz NM, Zehry HI, et al. Fluid administration in emergency room limited by lung ultrasound in patients with sepsis: protocol for a prospective phase Ⅱ multicenter randomized controlled trial[J]. JMIR Res Protoc, 2020, 9(8): e15997. doi: 10.2196/15997

[6] Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2021, 47(11): 1181-1247. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06506-y

[7] Egi M, Ogura H, Yatabe T, et al. The Japanese clinical practice guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2020 (J-SSCG 2020)[J]. J Intensive Care, 2021, 9(1): 53. doi: 10.1186/s40560-021-00555-7

[8] Jagan N, Morrow LE, Walters RW, et al. Sepsis, the administration of Ⅳ fluids, and respiratory failure A retrospective analysis—SAIFR study[J]. Chest, 2021, 159(4): 1437-1444. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.10.078

[9] Khan RA, Khan NA, Bauer SR, et al. Association between volume of fluid resuscitation and intubation in high-risk patients with sepsis, heart failure, end-stage renal disease, and cirrhosis[J]. Chest, 2020, 157(2): 286-292. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.09.029

[10] Meyhoff TS, Møller MH, Hjortrup PB, et al. Lower vs Higher fluid volumes during initial management of sepsis: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis[J]. Chest, 2020, 157(6): 1478-1496. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.11.050

[11] Moschopoulos CD, Dimopoulou D, Dimopoulou A, et al. New insights into the fluid management in patients with septic shock[J]. Medicina, 2023, 59(6): 1047. doi: 10.3390/medicina59061047

[12] Janotka M, Ostadal P. Biochemical markers for clinical monitoring of tissue perfusion[J]. Mol Cell Biochem, 2021, 476(3): 1313-1326. doi: 10.1007/s11010-020-04019-8

[13] 王雪婷, 高雪花, 曹雯, 等. 血乳酸联合Pcv-aCO2/Ca-cvO2及下腔静脉直径扩张指数指导脓毒症休克早期液体复苏治疗的价值[J]. 中国急救医学, 2020, 40(8): 703-708. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-ZJJY202008002.htm

[14] Ryoo SM, Lee J, Lee YS, et al. Lactate level versus lactate clearance for predicting mortality in patients with septic shock defined by sepsis-3[J]. Crit Care Med, 2018, 46(6): e489-e495. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003030

[15] Sneha K, Mhaske VR, Saha KK, et al. Correlation of the changing trends of ScvO2, serum lactate, standard base excess and anion gap in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock managed by early goal directed therapy (EGDT): a prospective observational study[J]. Anesth Essays Res, 2022, 16(2): 272-277. doi: 10.4103/aer.aer_52_21

[16] Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock(sepsis-3)[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(8): 801-810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287

[17] Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2017, 43(3): 304-377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6

[18] Malbrain ML, Martin G, Ostermann M. Everything you need to know about deresuscitation[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2022, 48(12): 1781-1786. doi: 10.1007/s00134-022-06761-7

[19] Lat I, Coopersmith CM, de Backer D, et al. The surviving sepsis campaign: fluid resuscitation and vasopressor therapy research priorities in adult patients[J]. Intensive Care Med Exp, 2021, 9(1): 10. doi: 10.1186/s40635-021-00369-9

[20] de Backer D, Aissaoui N, Cecconi M, et al. How can assessing hemodynamics help to assess volume status?[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2022, 48(10): 1482-1494. doi: 10.1007/s00134-022-06808-9

[21] 顾晓蕾, 张碧波, 邵杰, 等. 中心静脉-动脉血二氧化碳分压差联合乳酸清除率对感染性休克复苏指导意义的研究[J]. 中国急救复苏与灾害医学杂志, 2018, 13(2): 145-148. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-YTFS201802014.htm

[22] Kriswidyatomo P, Pradnyan Kloping Y, Guntur Jaya M, et al. Prognostic value of PCO2gap in adult septic shock patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Turk J Anaesthesiol Reanim, 2022, 50(5): 324-331. doi: 10.5152/TJAR.2021.21139

-

下载:

下载: